[I] Whether European, Chinese or Brazilian, art critics and commentators of Partenheimer’s work often point to the meditative, aerial, carefree, imaginative and even lyrical nature of his drawings and paintings, never failing to mention the enigmatic balance which makes his work and the silence that appears to inhabit it so highly recognizable (consider the Roman Diary, Carmen, De Coloribus, and Zur Grammatik series or Die fragilen…

The “cybernetic shift” that has been giving growing relevance since the 1960s to information (digital and/or genetic) in all spheres of human activity in order to reconfigure our understanding of life, work and knowledge, does not yet seem to have managed to trigger off in artists an awareness of the radical change of perspective it requires. Indeed, anyone frequenting contemporary art exhibitions and wishing to compare the boldness of what they see with the successive ruptures that the setting in motion of technoscience has brought about, cannot but feel horrified from the loss of a potential for transformation in a large number of aesthetic practices. The comparison clearly demonstrates that, faced by the strong economic and technoscientific acceleration, faced by that kind of total mobilization, to paraphrase Ernst Jünger, except for few exceptions, art seems to be losing any leading start it once had, at the very most striving to keep apace with that unbounded dynamics.

But, lets focus ourselves to genetic information, which seems to be what matters here. In recent years have witnessed the emergence of proposals of bio-art and transgenic art that endeavour to posit the problem of the relationships between nature and the “second nature” incorporated into the technosphere. However, these works are plagued with a certain inhibition or remain on the surface, not to say puerile, nature of their formulations which usually lose all charm and clout when the spectator “solves the riddle” or deciphers the idea behind the creation of the work. What is then revealed are simple applications of biotechnological principles or procedures, uncritically transplanted into the field of art, as in the case of Alba, the phosphorescent transgenic bunny by the Brazilian artist Eduardo Kac.

Now, the question takes on much more serious implications once we stop to consider the relationship between art and technology in Latin America. In this regard, clearly overlooking the huge social and biological diversity existing in some of our countries, artists do not seem to take on board the enormous aesthetic-political potential posed by the genetic resources of the continent, or their geopolitical, economic, environmental, social and cultural repercussions. The above-mentioned “cybernetic shift” moved reflection and experimentation to the molecular level of information, understood as “a difference that makes a difference,” as Gregory Bateson would have it, that is, as a resolution updating the power of the virtual. Apart from that, the “shift” helped us to understand that, on that level, plants, animals and human beings themselves could be regarded as singular arrangements of information, as specific operations processing the interactions of organisms and of those organisms with the medium, with the subsequent dissolution of identities into processes of individuation always in progress and never consolidated. Finally, the “shift” also made us realise that technoscience was very much interested in the modes and knowledge of indigenous peoples and of traditional communities, and how it was “associated” with the genetic resources available in that enormous biological diversity.

But, let us stop a bit longer on this point. Studying the question of invention from a technological paradigm and the notion of information, led the philosopher of technology Gilbert Simondon to discover that the ontogenesis of individuation in the fields of physics, biology and technology could be thought by means of a single theory capable of embracing the level of pre-individual reality from which all beings are individuated. In each one of those fields, invention appears when the information acts in the pre- individual intermediate reality that the philosopher calls “the consistent centre of being”, a both pre-vital and pre-physical natural reality that bears testimony to a certain continuity between the living being and inert matter and which also intervenes in the technical operation. As Simondon say,

“the technological object—conceived and built by man—does not limit itself to the creation of a mediation between man and nature. It is a stable combination of the human and the natural, it contains the human and the natural. (…) Technological activity (…) links man to nature.”[1]

[1] Simondon, G. Du monde d’existence des objets techniques, p. 245.

“The technological being can only be defined in terms of information and transformation of the various types of energy or of information. That is, on one hand as the vehicle of an action that goes from man to universe; and on the other, as the vehicle of an information that goes from the universe to man.”[2]

[2] Simondon, G. L’individuation psychique et collective, p. 283.

Simondon’s analysis establishes information as a real singularity providing consistence to inert matter, to the living creature (plant, animal, man), and to the technological artifact. And it would indeed be expedient to bring the philosopher’s formulation closer to the above-cited enlightening enunciation by Gregory Bateson. The possibility for a conception of a substratum that is common to inert matter, to the living being and to the technological object, gradually erases the limits between nature and culture erected by modern society. Furthermore, everything takes place as if there were a level of reality in which matter and human spirit could meet and engage in mutual communication, not as external realities in contact, but as systems that become integrated into a process of resolution that is immanent to the level itself. If technology is the vehicle of an action going from man to universe, and of information going from universe to man, it is also the resolution factor of an intense dialogue in which, rather than the pre-existent parts, what matters is the interaction, the productive nature of concatenation. Thus, at the very basis of the cybernetic shift we find man’s ability to “speak” the language of the “consistent centre of the being.”

Thus, the possibility to access, by means of information, to the level of pre-individual reality, a plane others classify as a virtual dimension of reality, will enable another understanding of individuation processes. Plants, animals, men and machine are beginning to be perceived as the outcome of an evolution which, rather than a result of adaptation, is the by-product of invention, a realisation of the potentials of the difference that makes the difference. Subsequently, the old borders separating nature and culture are falling down, therefore making it possible to make technological invention and the invention of nature compatible, for the two come from a common ground that allows us even to think of nature as design. Notwithstanding, it is also possible to establish a compatibility between invention understood from technology, and invention as seen by a shaman. Indeed, as Geraldo Andrello notes when studying the mythic narrative of the Tukano community: “the world as lived by indigenous people could well be described using the categories proposed by Simondon; his tale about the long period preceding the appearance of the first humans corresponds with a pre-individual reality, a world of potencies, resulting from a demiurgic ontology, and that is resolved as an individuation process.” The anthropologist believes that the role reserved by Simondon for information seems to be the same one played by difference in amazonian ontology, one which derives from the virtual background of potential affinity. And concludes,

“thus, we arrive to the basic question: if Simondon deserves a rereading today, certain ways of living, like those of the amazonian natives, would deserve to be assessed, for they turn ideas very close to those of the philosopher into the very basis of their societies and cultures. They do not make philosophy, however, they offer to us, among other things, a lived mythology that conveys a message concerning how to deal with the virtual, with difference, and possibly, with information.”[3]

[3] Andrello, G. “Gilbert Simondon na amazônia: notas a propósito do virtual”, in Nada, no. 7, March 2006, pp. 96 and ff.

All in all, everything seems to be happening as if Latin American artists had nothing to do with this new world that is opening up to an expanded perception of the tropical jungle as information, and of the transformation of the amazonian region (shared by Brazil, Peru, Colombia, Ecuador and Venezuela) into the scenario for a confrontation between the perspective of a global technoscience, and local, for instance amerindian, perspectives. Everything takes place as if artists were ignoring our own situation and condition, unable to perceive that it is precisely our singular insertion into the juncture that exists between nature and second nature that makes us a contemporary force. In that sense, it would perhaps be more productive for Latin American artists to rediscover themselves and their contexts as part of a wider dynamics, instead of following tendencies already outlined within the international art circuit, mimicking what is being made in the First World.

But, let me make one thing clear: i am not advocating any return to nationalism or to any other ism channelling art practices in an erroneous and hypothetical quest for our “essence.” That is not clearly the purpose, but rather that of investigating how new information technologies could help us to explore the technologies of nature, as well as to establish a fruitful dialogue with the traditional technologies of indigenous peoples and local communities. It is about questioning the possibilities of actualisation, here and now, of those potencies of the virtual dimension of reality that are already in operation in other latitudes and, naturally, in other directions.

Thus, to prevent any misunderstanding, it would perhaps be worthwhile to illustrate what i am trying to say by resorting to the example of a radical work that, at the same time, problematises the advances of technoscience, the issues affecting contemporary art, and the aesthetic-political conflicts emerging within the area of intersection between the two. And, given that this essay is part of a catalogue for an exhibition organised in Spain, i believe that its invocation here would be even more appropriate.

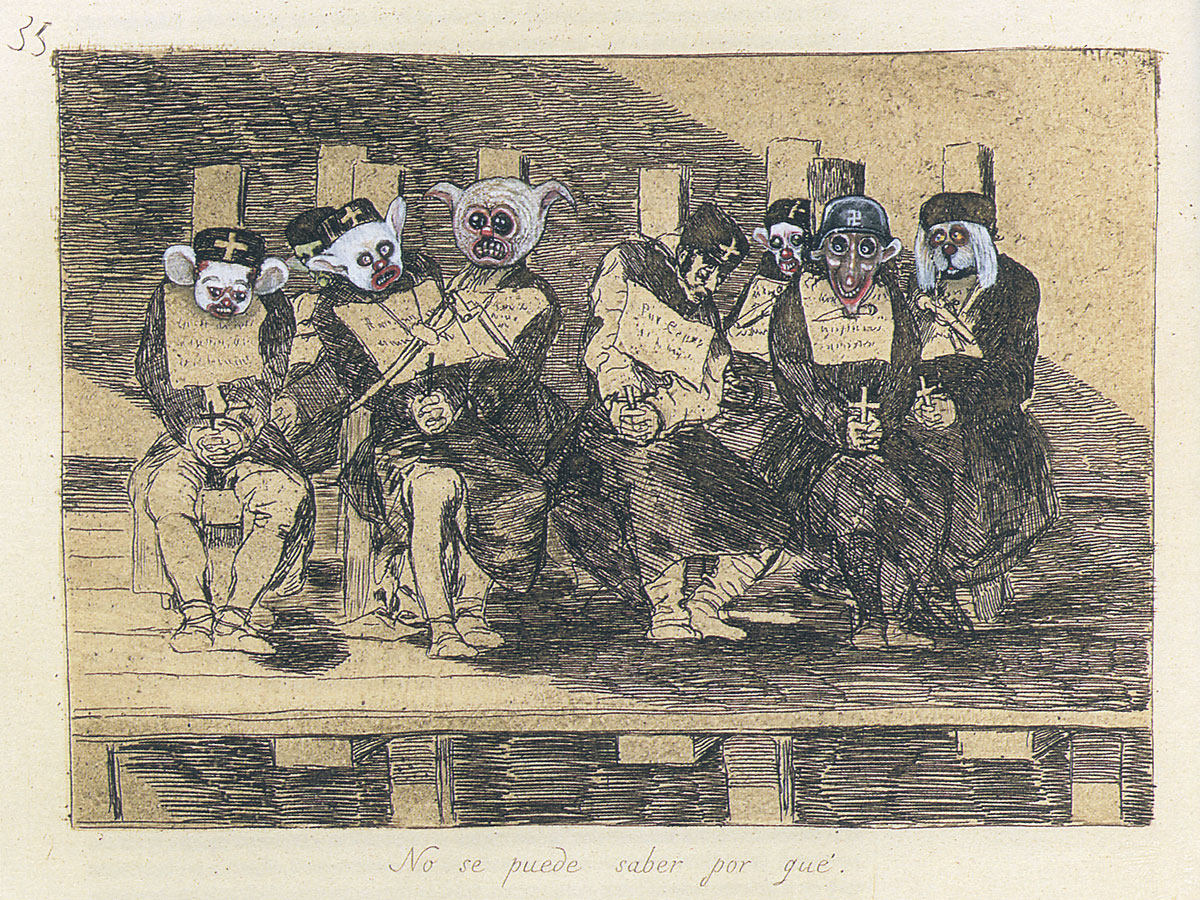

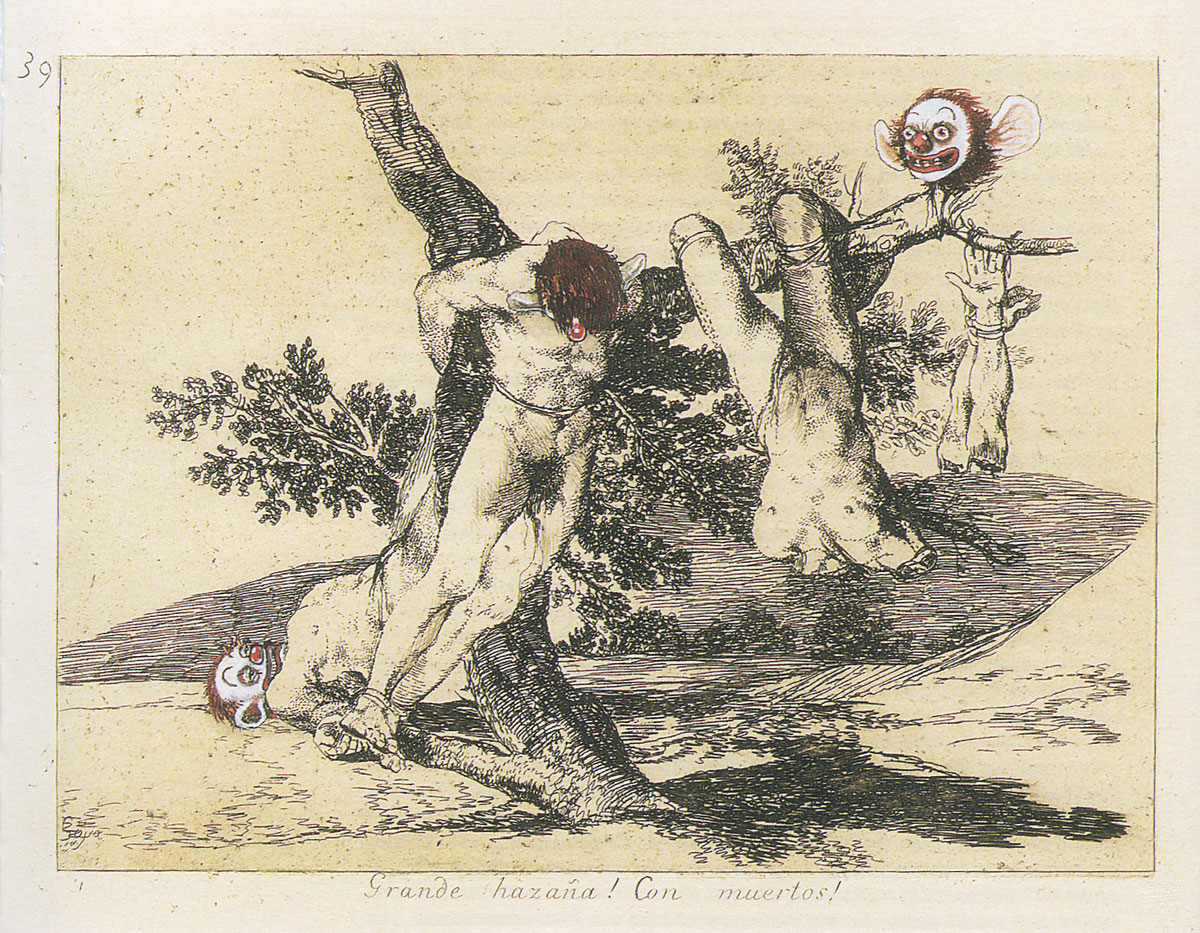

The example we have chosen is the work titled Insult to Injury by Jake and Dinos Chapman, exhibited in the first quarter of 2003 at Modern art oxford, in the show “The rape of creativity”, an ambiguous title for here, apart from its literal meaning, rape could also mean theft, extortion or an appropriation of creativity… The work features interventions made by the two British artists on original works from a complete series (80 etchings) of Goya’s Desastres de la Guerra (disasters of War), made between 1810 and 1815 and bought by the two artists for £25,000. Indeed, by painting heads of puppies, of a monkey or of clowns on the victims, by colouring with gouache the work of the great Spanish master, the Chapmans seem to have inflicted a direct attack on the sacred nature of masterworks in what many regarded as an act of “vandalism” equivalent to that of the Joker in Batman when he attacked all the paintings in a museum except for one by Francis Bacon…

In any case, how should we read the artistic gesture of the Chapmans? In an interview published in the Financial Times[4], Jake Chapman claimed that what turns Goya into such an exciting artist is, on one hand, the close contradiction between the artistic influence the enlightenment exerted on him, while, on the other, the violence exerted against his people in the name of reason. Chapman continued by saying that, although it is frequently claimed that this work is a depiction of atrocity, in his view Goya wanted, above anything else, to demonstrate how necessary violence is for reason, with those etchings describing the mechanisms of that ‘enlightened moral’ by which violence would be an effective means to demonstrate the absolute need for an ethical framework.

[4] See Monachesi, J. “Vandalismo conceitual”, Caderno Mais! Folha de São Paulo, 13th July 2003, pp. 4 and 5. See also “extensão do domínio da luta”, idem, pp. 6 and 7.

In any case, how should we read the artistic gesture of the Chapmans? In an interview published in the Financial Times[4], Jake Chapman claimed that what turns Goya into such an exciting artist is, on one hand, the close contradiction between the artistic influence the enlightenment exerted on him, while, on the other, the violence exerted against his people in the name of reason. Chapman continued by saying that, although it is frequently claimed that this work is a depiction of atrocity, in his view Goya wanted, above anything else, to demonstrate how necessary violence is for reason, with those etchings describing the mechanisms of that ‘enlightened moral’ by which violence would be an effective means to demonstrate the absolute need for an ethical framework.

“in his reactionary Spain, and in that monarchy, Goya shows a clear interest for French enlightenment. And then, something new eventually happens: the Lights, the revolution, but embodied in an occupation army and with all the horror of an occupation army. The peasants organise the first guerrillas to defend their lands under threat. They fight against a progress coming to meet them in the form of horror. And it is in that situation of tragic breach when the free-flowing paintbrush and the broken mark appears in Goya. There are no longer neat contours and decided touches with the paintbrush. It is a moment of rupture and also of the quivering of the stroke.”[5]

[5] in Müller, H. Guerre sans bataille, p. 231.

And then, do we have to make of such a negative horizon as this that, in the early days of the 21st century, enables to bring us back to the problems seen by Goya and encourages us to reassume it in a radical fashion? If Goya perceives a short circuit precisely in the moment that exemplified the movement from History to Utopia, as an anticipation of a future in which Utopia becomes History as the negative of what was expected of it, what short circuit would the Chapmans be trying to perceive? In other words, if we are living through a situation of horror today, what else could be done to define it, other than knocking down the borders of knowledge that separates science, art and thought from society?

With their prejudices, the critics prefer to conclude that the intention of the two english artists is just to provoke a scandal, or to establish an association between Insult to Injury with Duchamp’s “corrected” Mona Lisa, or with Rauschenberg’s Erased De Kooning Drawing, without taking into consideration the difference defining the gesture of the Chapmans. Indeed, when in 1919 Duchamp painted a moustache on a reproduction of Leonardo’s painting and wrote below it L.H.O.O.Q. (“elle a chaud au cul”, “She has a hot ass”), he made a work in which he invited the spectator to engage in a mental operation of demystification of the work of art through a “détournement”. The irreverence of a gesture simultaneously points at the rupture with a religious attitude vis-à-vis the history of art and to the transmition of creation from the canvas to the mind: the artwork no longer consisted of the materiality of its rendering, but was transformed into a concept. For all that, Duchamp preserves da Vinci’s painting when he intervenes in its image, restoring the possibility of looking at it with new eyes, removing the layers that the cult paid to it had placed over it. In turn, when, in 1953, Rauschenberg erased a drawing by De Kooning, he was not intervening in the image nor, strictly speaking, the work. The gesture points more at a dismantling of that image rather than its destruction or alteration, working as a statement. For Rauschenberg, it was about enunciating the need for a personal path while paying tribute to and, at the same time, recognising all that that path owes to the work of De Kooning. But when the Chapmans reconfigure the etchings by Goya, altering the very materiality of the original work, the question is different.

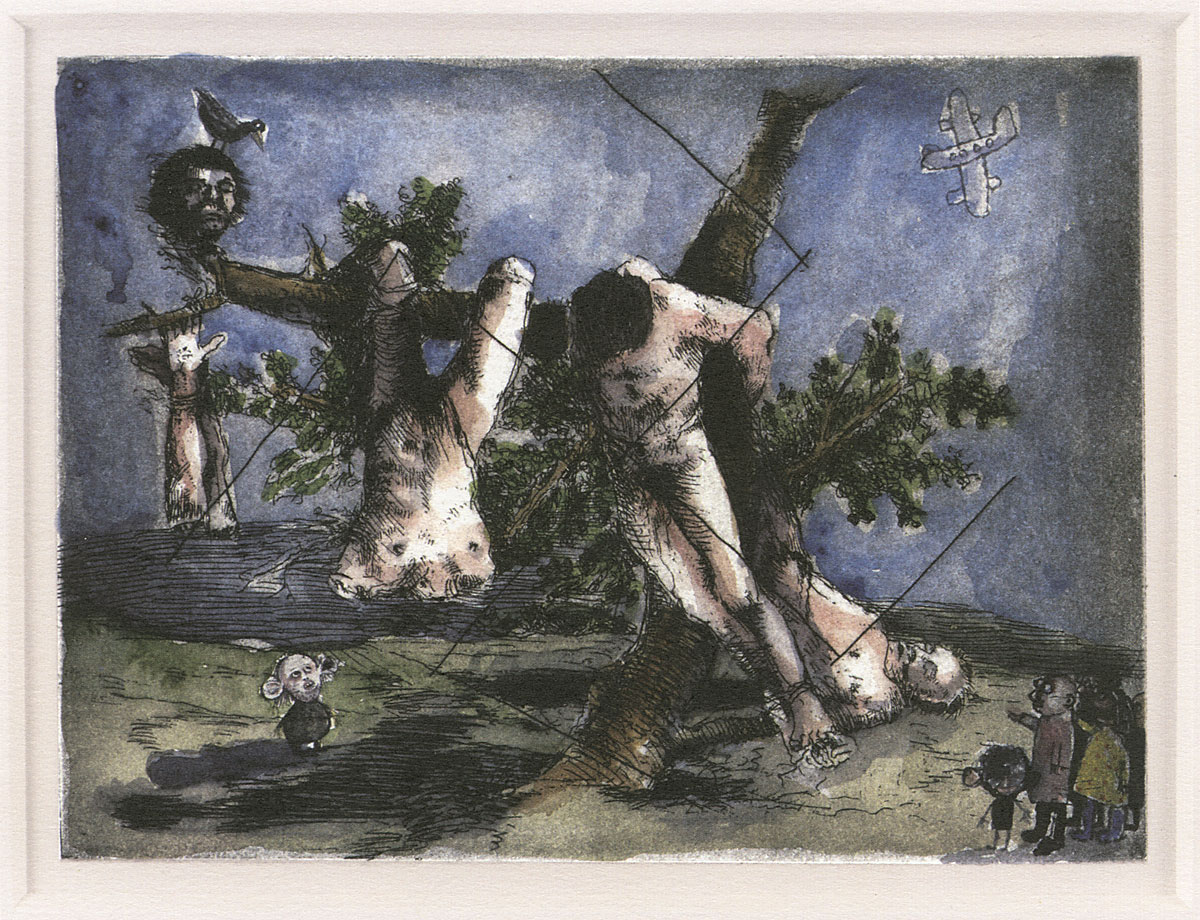

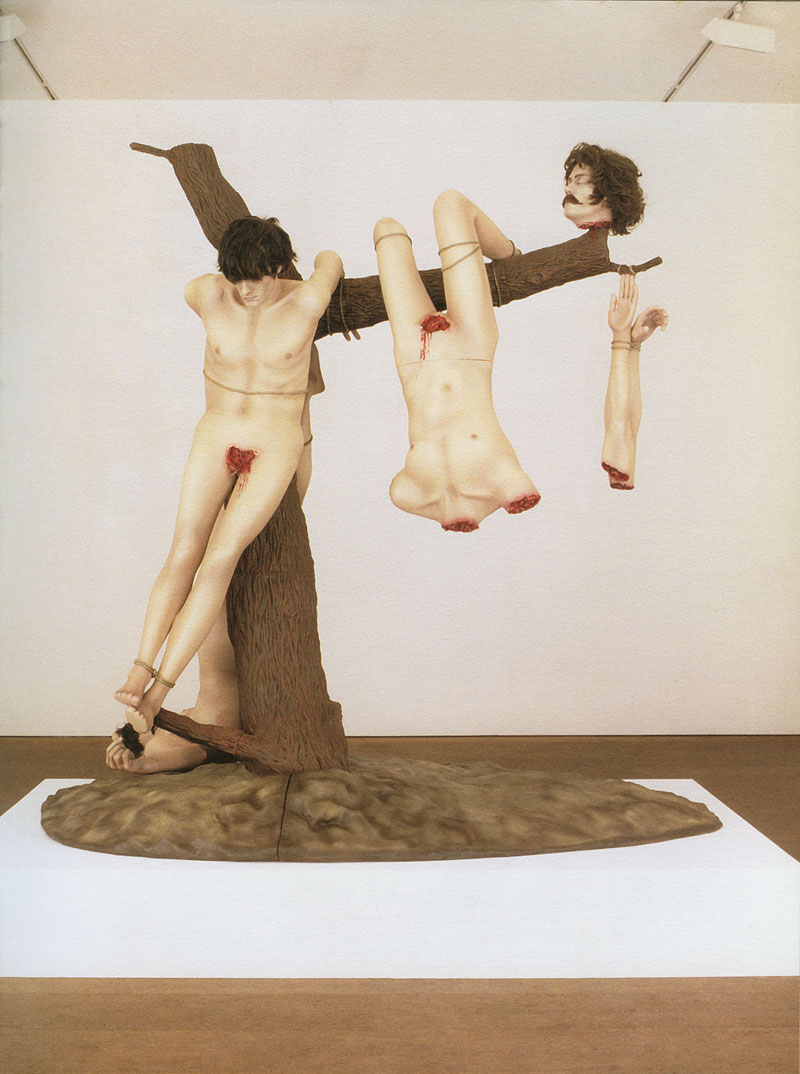

In the famous and controversial “Sensations” exhibition organised by the royal academy of arts of London in the second half of 1997, Jake and Dinos Chapman showed an installation titled Great Deeds Against the Dead, in fact a three-dimensional depiction of etching no. 39 from the Disasters of War, “Grande hazaña! Con muertos!” Goya’s etching depicts three dead bodies, mutilated and quartered, perhaps due to a supposed betrayal committed during Spain’s War of independence against the invading napoleonic forces. As Jesusa Veja explains, the historical documentation demonstrates that many individuals were suspected of betrayal and massacred by blind popular rage that saw them as collaborators with the foreign enemy. Veja writes:

“(…) it is not difficult to interpret who were those who committed such a great deed and who were the dead. Again, Goya crudely reflects on the results that may be expected from ignorant people, but this time he refrains from depicting an explicit image of that people. There is no action, and the etching is, in fact, ‘a monument to barbarity and atrocity,’ extolling the nobility and dignity of those mutilated bodies, over which he throws light showing the unfair torment they were subjected to. (…) By representing this ‘spectacle’, Goya’s intention was not to horrify our vision – the victims’ faces express even the tranquillity and the beautiful proportions of some bodies inviting to be contemplated; on the contrary, Goya tries to provoke a reflection before those images: that great deeds can never be the result of the excesses of a ‘blood-thirsty cruelty’, or of an excess of ‘heroism’ or of ‘a love of the mother country”.[6]

[6] See Goya y el espíritu de la Ilustración. Exhibition catalogue. Madrid: Museo del prado, 1988, pp. 306-307.

By revisiting the work of the Spanish painter, the two English artists start, before any other thing, by removing the exclamations describing this disaster: Great Deeds! Against the Dead! is turned into Great Deeds Against the Dead. It is as if, by emphasising the reflective nature of the work, they underline all the horror existing in death and in the mutilation of bodies, and, by doing so, they put the stress on the tension between nature and culture, that is, between the individuals inasmuch as living beings, and the subjects inasmuch as victims of History and, within each one of those poles, the tension existing between violence and reason. The reflection is thus amplified: the “great deed” is no longer circumscribed to a specific historical context, to the tragedy of a society maddened to the point of self-devouring itself, destroying its own children, in order to transform it into the destruction of the human being as such by virtue of the universal expansion of enlightenment as a negative horizon. It is as if the reason of violence was equal to the violence of reason! As if the short circuit detected by Goya had de- territorialised itself in order to gain unsuspected dimensions! Tied and hanging from the tree, emasculated and cut into pieces, the bodies are depicted as the result of a major operation of disjuncture.

An operation whose charge, on the other hand, is only fully legible after linking it with another three works by the Chapmans included in that exhibition: Ubermensch, an installation depicting nietzsche’s superman in the body of the physicist Stephen Hawkings, seen seated on a wheelchair holding his laptop and on the top of a rock; Zygotic acceleration, biogenetic, de-sublimated libidinal model, a group of mannequins of girls mutually connected by their intertwined torsos, wearing designer sports shoes that underline their contemporaneity and whose existence is justified as an absurd and phantasmatic object of desire, considering their sexual polymorphism, made possible through a displacement of their genitals and through the many promises of sexual pleasure that the implanted penises, vaginas, heads and anuses might be offering; finally, Tragic Anatomies, an installation showing a kind of Garden of delights in which a number of mannequins – whose bodies describe various combinations of Siamese twins – inviting the spectator to relish the spectacle of some unseen and highly usual baigneuses, resonating with the tradition of painting.

Obviously, the Chapman brothers were engaged in discussion about the paradoxes of technoscience in contemporary art and society, and more specifically, about the aspirations, desires and fantasies biotechnology evokes. All in all, there is a difference between the works exhibited in “Sensations” and Insult to Injury. In the former, the relationship between violence and reason was expressed in the object and in the image displayed before the gaze, as if the artists were trying to materialise and to make visible the operation of destruction and recombination of the bodies and their organs by technoscience, and their implications for the human being; in contrast, in the latter, the intention is to do, in the field of art, exactly what is being done in biotechnology labs, so the spectator may become aware of the reach of the operation. Indeed, why should the intervention on Goya’s originals be deemed as offensive and turned into a scandal? Precisely because they are original etchings, and not reproductions. The Chapmans made an appropriation of the etchings, and through the introduction of elements that were alien to them, they definitively altered the composition of the whole, irreversibly transforming, as a result, the value of that element of heritage. It is as if the etching by Goya were a rare and precious genome, with singularities and virtualities eliciting the temptation of reinvention, a new design capable of fostering a new actualisation. A Transgenic art par excellence, not only in its visible renditions, but mainly in the procedures with which it operates, the work of the two English artists makes us wonder if the recombination of an art masterpiece would not be a demonstration of the meaning of the recombination of vegetal and animal species, and even of human bodies, understood by the artists as masterpieces of evolution, that have now become susceptible of being recreated.

Insult to Injury is, obviously, a great provocation. However, i do believe that we need provocations at the level of the gauntlet thrown down by the “cybernetic shift.” Biotechnology is producing a major displacement in our perception of life. Biotechnology’s association/disassociation with biodiversity in Latin America anticipates the transformations taking place in the region. And it is down to artists to express them in aesthetic and political terms.

Text for the catalogue published for the exhibition EMERGENTES at LABoral Centro de Arte y Creación Industrial, Gijón, from 16 November 2007 through 12 May 2008. (ISBN: 978-84-612-1959-9)

© of photographs: the authors

This post is also available in:

![]() Português (Portuguese (Brazil))

Português (Portuguese (Brazil)) ![]() Español (Spanish)

Español (Spanish)